예수 삼부작과 코다 Jesus Trilogy and Coda, The_스탠 브래키지 Stan Brakhage

예수 삼부작과 코다 Jesus Trilogy and Coda, The_스탠 브래키지 Stan Brakhage

US / 2001 / Color / Silent / 20 min / 16mm

2023년 7월 26일(수) 오후 7시

Wed. Jul 26, 2023 at 7:00pm

@ 한국영상자료원 시네마테크KOFA 2관

Korea Film Archive Cinematheque KOFA Theater 2

Description

The Jesus Trilogy and Coda is composed of the four following parts:

(1) IN JESUS NAME presents an almost continuous fluttering movement midst the complexity of multiple small shapes in mostly autumnal colors, like unto a wind moving through fall leaves. Embedded in this skein (almost as if branches of this scene) are the dark lines ephemerally (almost invisibly) composing the conventional face of Christ.

(2) THE BABY JESUS begins with pearl-pinks and gold-flecked shapes midst 'garden greens'. It proceeds to contrasting desert scenery - slashes of sand-yellow under black 'sky', with ephemeral suggestions of animal locomotion. Then there's some sense of darkened interior, the colors of straw and wood, slight furtive hints of beast features, hooded 'faces' and swaddling folds. Rolling hills, and a starred 'night sky' with flecks of herded white, then a gathereing (sic) of colors as of collected people shapes. After interveening (sic) black, the beseeming rocky side of a hill increasingly flecked with blood-red. The desert-likeness comes again with, again, animal-like locomotion. Mills, mottled white, like snow, give way finally to peacefully wood-toned enclosures.

(3) JESUS WEPT utilizes a variety of shapes and colors so fretted and interlocked with darkness as to create the sense of a glamorous terror within which palpable shapes of 'tears' appear and weave a counterbalance of sorrowful calm. Because these 'tears' are as if in bas-relief (side and front lit), textured and altogether of such a visual solidity, they form and (sic) aesthetic bulwark against the (back lit) fret of forms.

(4) CODA: CHRIST ON CROSS contains the most easily nameable of all the shapes in this trilogy: it is, thus, an aesthetic 'summing-up' with full emphasis upon the crucifixion which is visible again and again as a mass of twisting lines and tortured forms, flecked with vermillion blood-likeness. The interveening (sic) scenes are stark, dark dramatics, reactive to the recurring cross. The conventional face of Jesus is occasionally visible as lines that are consonent (sic) with the, at times, almost renaissance draftsmanship of these scenes. The attempt is to sum-up Death as iconic triumph in relation to the three previous films.

예수 삼부작과 코다는 다음 네 부분으로 구성된다.

(1) ‘예수 이름으로’는 마치 바람이 낙엽 사이로 지나가는 것처럼 주로 가을 색상의 된 여러 작은 모양의 복잡성 속에서 거의 연속적으로 펄럭이는 움직임을 보여준다. 이 실타래에 있는(마치 이 장면의 가지처럼) 어두운 선이 일시적으로(거의 보이지 않게) 그리스도의 전통적인 얼굴을 구성한다.

(2) ‘아기 예수’는 '정원의 녹색' 사이에서 진주 핑크와 금빛 반점 모양으로 시작한다. 그것은 대조적인 사막 풍경 - 검은 '하늘' 아래의 모래-노란색의 슬래시, 동물의 이동에 대한 순간적인 제안으로 이어진다. 그리고 어두운 내부의 느낌, 짚과 나무의 색깔, 짐승의 특징의 은밀한 암시, 후드를 쓴 '얼굴'과 포대기 주름이 있다. 구불구불한 언덕들, 그리고 하얀 반점들이 있는 별이 표시된 '밤 하늘', 그리고 모여든 사람들의 모양과 같은 색깔들의 모임. 검은 색이 교차한 후, 언덕의 뾰족해 보이는 바위 쪽이 점점 핏빛으로 물들었습니다. 사막과 같은 것이 동물과 같은 이동과 함께 다시 온다. 눈처럼 얼룩덜룩한 하얀 제분소들이 마침내 평화로운 나무색 인클로저에 자리를 내준다.

(3) ‘예수의 눈물’은 다양한 모양과 색깔을 사용하여 어둠과 연결되어 눈에 띄는 '눈물'의 모양이 나타나고 슬픔에 찬 고요함의 균형을 짜내는 매혹적인 공포감을 조성한다. 이 '눈물'은 마치 얕은 부조(측면 및 전면 조명)에 있는 것처럼 질감이 있고 시각적인 견고함을 함께 가지고 있기 때문에 (후면 조명) 형태의 초조함을 방지하는 미학적인 장벽을 형성한다.

(4) ‘코다: 십자가 위의 그리스도’는 이 3부작의 모든 모양 중에서 가장 쉽게 이름을 붙일 수 있는 것들을 포함하고 있다. 따라서, 그것은 수백만 개의 피처럼 얼룩진 뒤틀린 선과 고문된 형태의 덩어리로 반복해서 보이는 십자가형을 완전히 강조하는 미학적 '총합'이다. 저녁의 장면은 삭막하고 어두운 드라마틱하며 반복되는 십자가에 반응한다. 예수의 전통적인 얼굴은 때때로 이 장면들의 거의 르네상스적인 초안 작업과 구성되는 선으로 가끔 보인다. 그 시도는 이전 세 편의 영화와 관련하여 죽음을 상징적 승리로 요약하는 것이다.

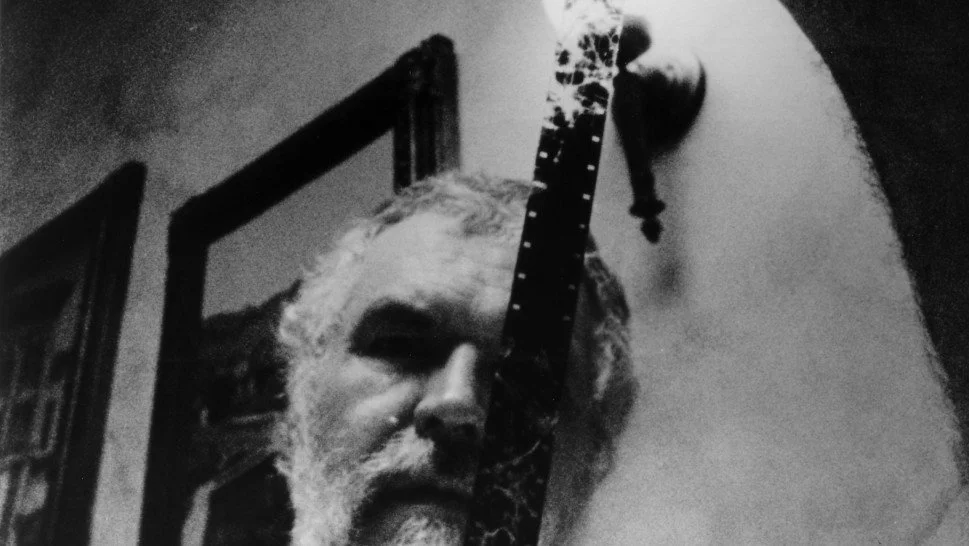

Bio

He always resisted systems and nourished contradictions, so that his work would remain alive. Still, there is a consistent theoretical basis for his enormous work. Starting from the premise that cinema was the first means humans ever had to represent directly the unceasing scanning movements of the eyes, Brakhage made eye movement the cornerstone of his art. This entailed, first of all, an apperceptive discipline of studying his own eye movements through the range of his moods, crises, and joys. The resulting sensitivity to shifts of focus, phosphene activity on the surface of the eye, and peripheral vision helped him to develop an astonishingly flexible shooting style. Often he enhanced or adjusted the film he shot with superimpositions, hand-painting, by scratching the emulsion, or by incorporating negative.

From Metaphors on Vision we can derive the following principles: (1) the eyes are always moving, scanning in response to all visual stimuli; (2) vision never stops; the eyes see phosphenes when closed, dreams when asleep; (3) the names for things and for sensible qualities blunt our vision to nuances and varieties in the visible world; (4) normative religion hypostatize the power of language oversight ("In the beginning was the word") in order to legislate behavior through fear; (5) the self-conscious and responsible use of language is poetry; (6) only through an educated and comprehensive encounter with literature can a visual artist hope to gain release from the dominance of language overseeing; there can be no naive, untutored vision. (7) The artist is repeatedly challenged to sacrifice the gratifications of the ego and the will to the unpredictable demands of his or her art.

The cumulative project of Brakhage's cinema was the visual life articulated over many years. He was convinced that there was a primary level of cognition that preceded language which he came to call "moving visual thinking" in his later theoretical writings. It was the unconscious of vision, which he aspired to make visible. He was not naïve about the contradictions of this goal; his films always acknowledged the material limitations of cinematic representation. His role in the process of filmmaking was essentially to let the cinema articulate itself through him. By clearing the conduits of preconceptions, ambitions, purposes, the films would emerge through him. So, they were at once the most personal, most subjective of all films and more fundamentally expressions of a pure primary process-cinema unfolding its own secret life.

The range of themes was staggering: epic myths, shimmering lights, an autopsy, visions of the afterlife, haunted ruins, sexual fantasies, war as a media event, the ache of childhood memories, travel, nightmares, the ritual origins of sports events, angels, and all the aspects of family life. He married twice. First to Jane Collom (now author Jane Wodening). He filmed the birth of all five of their children and the effective lives of the numerous animals she raised, studied, and made the subjects of her short stories. The breakup of that marriage, his loneliness, and eventually his love for Marilyn Jull and their union can be traced through many of his films of the 1980s. They had two children but she did not want him to make their family life the direct subject of his work. Inspired and, he said, relieved by the prescription, he evoked their shared experience in dozens of hand-painted films and pursued evocations of Marilyn's presence filming the places she had lived.

The night he died, Jonas Mekas telephoned me: "It feels like an era has ended." Mekas is always so reticent about the deaths of our friends. I had never heard him say anything like that in the fifty years I've known him. Nathaniel Dorsky called too: he couldn't bring himself to shoot film the next day, knowing that Brakhage could no longer film. Even though we knew this death was imminent the shock comes in realizing that the outpouring of films has ceased. For five decades we could always count on new Brakhage films, in the bleakest years, to affirm the continuity of the art. Nothing could stop him but death. (P. Adams Sitney)

그는 언제나 체계에 저항했고, 모순을 키우고, 그래서 그의 작품은 생명력을 유지할 수 있다. 여전히 그의 엄청난 양의 작품에는 일관된 이론적 기반이 존재한다. 영화가 인간의 눈의 계속되는 움직임을 직접적으로 재현하는 최초의 수단이라는 가정 하에 브래키지는 눈의 움직임을 자신의 예술작품의 초석으로 삼았다. 그는 우선 통각적 관점에서 기분, 곤란함, 즐거움의 정도에 따른 자기 눈의 움직임을 연구하였다. 그리고 이를 확장하여 안구 표면에서 일어나는 안내 섬광 현상, 그리고 주변 시야에 초점을 맞추게 되면서 놀라운 촬영 기법으로 발전하게 되었다. 그는 주로 다중 인화와 노출, 핸드-프린팅, 필름 에멀전 스크래치, 네거티브 이미지의 결합 등을 통해 영화를 확장하고 변형시켰다. <시각에 대한 메타포>로부터 우리는 다음의 원칙을 도출할 수 있다. (1) 눈은 모든 시각적 자극에 반응하면서 언제나 움직인다. (2) 시각은 멈추지 않는다. 눈을 감으면 안내 섬광이 보이고 잠을 자면 꿈을 꾼다. (3) 사물의 이름과 감각적 능력은 오히려 보이는 세계의 뉘앙스와 다양성을 인지할 수 있는 능력을 감퇴시킨다. (4) 규범적 종교는 언어의 힘을 실체화해서 공포를 통해 우리의 행태를 감독하려 한다. (5) 언어의 자의식이자 책임감 있는 사용을 가능하게 하는 것은 ‘시’ 언어다. (6) 언어적 제약으로부터 벗어나기 위해서 시각예술가는 ‘문학’에 대한 포괄적 교육을 받아야 한다. (7) 예술가는 자신의 예술이 요구하는 예측불가능한 요구에 대해 자아의 쾌락을 희생하도록 반복적으로 도전받는다.

브래키지 영화의 누적적 기획은 여러 해 동안 연결된 시각적 삶을 표현한다. 그는 언어에 앞서는 원시적 수준에서의 인지활동이 존재한다고 믿었고 그는 이를 나중에는 “움직이는 시각 사고"라고 불렀다. 그것은 바로 시각의 무의식으로서, 그는 이를 시각화하고자 했다. 그는 이러한 목표가 모순을 함축하고 있다는 점을 알고 있었다. 그의 영화 작품은 언제나 영화적 재현의 물질적 한계를 인식하고 있다. 영화제작 과정에서 그의 역할은 영화가 작가를 통해서 표현되도록 하는데 있다. 선입관, 야심, 의도 등이 반영되는 것을 막으면서 그는 영화가 자신을 통해서 형성되도록 했다. 그렇게 해서 그의 작품은 동시에 가장 사적이고 주관적인 영화이면서 더욱 근본적으로는 자신의 비밀스런 삶을 들춰내는 순수한 최초의 과정으로서의-영화의 표현이 되었다.

작품의 테마의 범위는 상당했다. 서사적 신화에서부터 희미한 빛, 시체 부검, 사후세계의 모습, 을씨년스런 폐허, 성적 판타지, 미디어 이벤트로서의 전쟁, 어린 시절 기억의 아픔, 여행, 악몽, 스포츠 행사의 제례적 기억, 그리고 가족 생활의 다양한 측면에 이르기까지 다양한 테마를 다루고 있다. 그는 두 번 결혼했다. 첫 번째 결혼은 제인 컬럼(현재는 작가인 제인 워드닝)과 했다. 그는 다섯 아이의 출산, 그리고 제인이 기르고 연구하고 단편소설의 소재로 삼았던 여러 동물의 삶을 촬영했다. 결혼 생활의 파탄, 외로움, 그리고 이후의 마릴린 줄과의 사랑과 결혼은 1980년대의 그의 여러 작품을 통해서 추적할 수 있다. 그들은 두 아이를 가졌지만, 마릴린은 그가 가족의 삶을 직접적인 작품의 대상으로 삼지 않기를 원했다. 그래서 그는 공동의 경험을 떠올리게 해주는 다수의 핸드-프린팅 작품을 만들었고, 마릴린의 현전을 그녀가 살았던 곳을 촬영함으로써 대신하였다.

그가 세상을 뜬 날 밤에 요나스 메카스는 내가 전화를 했다. “한 시대가 끝난 느낌이다.” 메카스는 언제나 친구들의 죽음에 대해서 극도로 말을 아꼈다. 내가 그를 알고 지낸 50여년 간 그는 한 번도 이런 말을 한 적이 없었다. 내서니얼 도스키도 전화를 했다. 그는 그 다음날 브래키지가 더 이상 촬영을 하지 못한다는 사실 때문에 자신도 촬영을 하러 가지 못했다. 우리는 그가 죽었다는 사실을 알고 있었지만, 더 이상 계속해서 작품이 만들어지지 않는다는 사실에 충격을 받았다. 50년 동안 우리는 언제나 브래키지의 새로운 작품을 기대했고, 예술이 계속된다고 확신할 수 있었다. 죽음만이 그를 멈추고 말았다. (P. 애덤스 시트니)